Oświadczenie

Dr Scheiman był zatrudniany jako konsultant w AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, Merck & Co, Inc., Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Inc., Pozen, Inc., Bayer, GlaxoSmithKline, Inc., PLx Pharma, Inc., NiCox, Horizon Therapeutics i TAP Pharmaceutical Products, Inc. i otrzymywał honoraria za wykłady dla AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. i Santarus, Inc.

© Copyright 2009 Current Medicine Group LLC, a division of Springer Science & Business Media LLC i Medical Tribune Polska Sp. z o.o. Wszystkie prawa zastrzeżone w języku polskim i angielskim. Żadna część niniejszej publikacji nie może być gdziekolwiek ani w jakikolwiek sposób wykorzystywana bez pisemnej zgody Current Science Inc. i Medical Tribune Polska Sp. z o.o. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in any information retrieval system, or transmitted in an electronic or other form without prior written permission of Current Medicine Group LLC and Medical Tribune Polska.

Piśmiennictwo

1. Scheiman JM: Gastroduodenal safety of COX-2 specific inhibitors. Curr Pharm Des 2003, 9:2197-2206.

2. Scheiman JM, Fendrick AM: Practical approaches to minimizing gastrointestinal and cardiovascular safety concerns with COX-2 inhibitors and NSAIDs. Arthritis Res Ther 2005, 7(Suppl 4):S23-S29.

3. Hernandez-Diaz S, Garcia Rodriguez LA: Association between nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding/perforation. Arch Intern Med 2000, 160:2093-2099.

4. Fries S, Grosser T, Price TS, et al.: Marked interindividual variability in the response to selective inhibitors of cyclooxygenase-2. Gastroenterology 2006, 130:55-56.

5. de Abajo FJ, Montero D, Rodriguez LA, et al.: Antidepressants and risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2006, 98:304-310.

6. Piper JM, Ray WA, Daugherty JR, et al.: Corticosteroid use and peptic ulcer disease: role of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Ann Intern Med 1991, 114:735-740.

7. Shorr RI, Ray WA, Daugherty JR, et al.: Concurrent use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and oral anticoagulants places elderly persons at high risk for hemorrhage peptic ulcer disease. Arch Intern Med 1993, 153:1665-1670.

8. Wallace JL, McKnight W, Reuter BK, et al.: NSAIDsinduced gastric damage in rats: requirement for inhibition of both cyclooxygenase 1 and 2. Gastroenterology 2000, 119:706-714.

9. Silverstein FE, Faich G, Goldstein JL, et al.: Gastrointestinal toxicity with celecoxib vs. nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: the CLASS study: a randomized controlled trial. Celecoxib Long-term Arthritis Safety Study. JAMA 2000, 284:1247-1255.

10. Bombardier C, Laine L, Reicin A, et al.: Comparison of upper gastrointestinal toxicity of rofecoxib and naproxen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. VIGOR Study Group. N Engl J Med 2000, 343:1520-1528.

11. Mamdani M, Juurlink DN, Kopp A, et al.: Gastrointestinal bleeding after the introduction of COX 2 inhibitors: an ecological study. BMJ 2004, 328:1415-1416.

12. Deeks JJ, Smith LA, Bradley MD: Efficacy, tolerability, and upper gastrointestinal safety of celecoxib for treatment of osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. BMJ 2002, 325:619.

13. Farkouh ME, Kirshner H, Harrington RA, et al.: Comparison of lumiracoxib with naproxen and ibuprofen in the Therapeutic Arthritis Research and Gastrointestinal Event Trial (TARGET), cardiovascular outcomes: randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004, 364:675-684.

14. Antman EM, Bennett JS, Daugherty A, et al.: Use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs an update for clinicians: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2007, 115:1634-1642.

15. Scheiman JM, Fendrick AM: Summing the risks of NSAID therapy. Lancet 2007, 369:1580-1581.

16. Grosser T, Fries S, FitzGerald GA: Biological basis for the cardiovascular consequences of COX-2 inhibition: therapeutic challenges and opportunities. J Clin Invest 2006, 116:4-15.

17. Jüni P, Nartey L, Reichenbach S, et al.: Risk of cardiovascular events and rofecoxib: cumulative meta analysis. Lancet 2004, 364:2021-2029.

18. Bresalier RS, Sandler RS, Quan H, et al.: Cardiovascular events associated with rofecoxib in a colorectal adenoma chemoprevention trial. N Engl J Med 2005, 352:1092-1102.

19. Nussmeier NA, Whelton AA, Brown MT, et al.: Complications of the COX-2 inhibitors parecoxib and valdecoxib after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med 2005, 352:1081-1091.

20. Solomon SD, McMurray JJ, Pfeffer MA, et al.: Cardiovascular risk associated with celecoxib in a clinical trial for colorectal adenoma prevention. N Engl J Med 2005, 352:1071-1080.

21. Arber N, Eagle CJ, Spicak J, for the PreSAP Trial Investigators: Celecoxib for the prevention of colorectal adenomatous polyps. N Engl J Med 2006, 355:885-895.

22. PRECISION: Prospective randomized evaluation of celecoxib integrated safety vs ibuprofen or naproxen. http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct/show/NCT00346216;jsessionid=D55628B7B188792A5D69CD83784575F1?order=10. Accessed April 25, 2007.

23. Kearney PM, Baigent C, Godwin J, et al.: Do selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors and traditional non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs increase the risk of atherothrombosis? Meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ 2006, 332:1302-1308.

24. ADAPT Research Group: Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events in the randomized, controlled Alzheimer’s Disease Anti-inflammatory Prevention Trial (ADAPT). PLoS Clin Trials 2006, 1:e33.

25. Silverstein FE, Graham DY, Senior JR, et al.: Misoprostol reduces serious gastrointestinal complications in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1995, 123:241-249.

26. Hawkey CJ, Karrasch JA, Szczepanski L, et al.: Omeprazole compared with misoprostol for ulcers associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. N Engl J Med 1998, 338:727-734.

27. Graham DY, Agrawal NM, Campbell DR, et al.: Ulcer prevention in long-term users of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: results of a double-blind, randomized, multicenter, active- and placebo-controlled study of misoprostol vs lansoprazole. Arch Intern Med 2002, 162:169-175.

28. Chan FK, Hung LC, Suen BY, et al.: Celecoxib versus diclofenac and omeprazole in reducing the risk of recurrent ulcer bleeding in patients with arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2002, 347:2104-2110.

29. Chan FK, Hung LC, Suen BY, et al.: Celecoxib versus diclofenac plus omeprazole in high-risk arthritis patients: results of a randomized double-blind trial. Gastroenterology 2004, 127:1038-1043.

30. Scheiman JM, Yeomans ND, Talley NJ, et al.: Prevention of ulcers by esomeprazole in at-risk patients using non-selective NSAIDs and COX 2 inhibitors. Am J Gastroenterol 2006, 101:701-710.

31. Chan FK, Wong VW, Suen BY, et al.: Combination of a cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor and a proton pump inhibitor for the prevention of recurrent ulcer bleeding in patients with very high gastrointestinal risk: a double-blind, randomized trial. Lancet 2007, 369:1621-1626.

32. Lanas A, García-Rodríguez LA, Arroyo MT, et al.: Effect of antisecretory drugs and nitrates on the risk of ulcer bleeding associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antiplatelet agents, and anticoagulants. Am J Gastroenterol 2007, 102:507-515.

33. Ray WA, Chung CP, Stein CM, et al.: Risk of peptic ulcer hospitalizations in users of NSAIDS within gastroprotective cotherapy versus coxibs. Gastroenterology 2007, 133:790-798.

34. Spiegel BM, Chiou CF, Ofman JJ: Minimizing complications from nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: cost-effectiveness of competing strategies in varying risk groups. Arthritis

Rheum 2005, 53:185-197.

Komentarz

prof. dr hab. med. Andrzej Dąbrowski, Klinika Gastroenterologii i Chorób Wewnętrznych UM, Białystok

prof. dr hab. med. Andrzej Dąbrowski

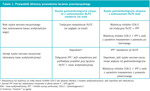

Rycina 1. Poziom ryzyka gastrotoksyczności NLPZ wywołanego przez różne czynniki

Artykuł Jamesa M. Scheimana na temat zapobiegania owrzodzeniom spowodowanym przez niesteroidowe leki przeciwzapalne (NLPZ) jest praktycznym przewodnikiem po współczes-nych zasadach gastroprotekcji. NLPZ mogą uszkadzać różne fragmenty przewodu pokarmowego, ale żołądek jest najbardziej narażony na efekty toksyczne tych leków. Uszkodzenie żołądka jest następstwem blokowania syntezy prostaglandyn, które stymulują mechanizmy ochronne błony śluzowej tego narządu. Wykazano, że nawet niewielkie, a wręcz mikroskopijne dawki kwasu acetylosalicylowego (10 mg), który blokuje COX-1 i COX-2, powodują dramatyczne zahamowanie (do ok. 40% normy) syntezy prostaglandyn w błonie śluzowej żołądka, podczas gdy ta sama dawka nie wpływa na ich poziom w śluzówce dwunastnicy lub odbytnicy.1 Naturalnym sposobem gastroprotekcji byłoby więc szerokie stosowanie pochodnych prostaglandyn. W praktyce są one jednak stosowane niezmiernie rzadko zarówno ze względu na ich bardzo wysoką cenę, jak i objawy niepożądane. Złotym standardem w gastroprotekcji pozostają więc inhibitory pompy protonowej (IPP). Warto zwrócić uwagę, że satysfakcjonujący poziom ochrony żołądka zapewniają dopiero standardowe dawki IPP. Pozwolę sobie przypomnieć, że za dawki standardowe uznaje się: 40 mg ezomeprazolu, 30 mg lanzoprazolu, 20 mg omeprazolu, 40 mg pantoprazolu i 20 mg rabeprazolu. Gastroprotekcja za pomocą IPP jest zalecana u osób ze zwiększonym ryzykiem toksycznych objawów działania NLPZ. Rycina 1 ilustruje poziom tego ryzyka wywoływanego przez różne czynniki.

Rycina 2. Algorytm postępowania w przypadku uszkodzenia przewodu pokarmowego w czasie terapii NLPZ i lekami antyagregacyjnymi

W erze stosowania na coraz szerszą skalę NLPZ, kwasu acetylosalicylowego i innych leków antyagregacyjnych – głównie klopidogrelu – problem skutecznej gastroprotekcji staje się bardzo istotny. W ubiegłym roku opublikowano godny uwagi konsensus ekspertów amerykańskich towarzystw kardiologicznych i gastroenterologicznych (ACCF/ACG/AHA) poświęcony zmniejszaniu ryzyka uszkodzenia przewodu pokarmowego w czasie terapii z zastosowaniem NLPZ i leków antyagregacyjnych.2 Rycina 2 ilustruje algorytm proponowany przez autorów konsensusu. Warto zwrócić uwagę, że w algorytmie znajduje się również opcja uwzględniająca istotną rolę zakażenia H. pylori w zwiększaniu ryzyka gastrotoksycznych efektów NLPZ i leków antyagregacyjnych.

W związku ze stosowaniem tego algorytmu na coraz szerszą skalę należy zwrócić uwagę na niepokojące informacje dotyczące możliwej interakcji klopidogrelu i IPP. Sugeruje się, że wśród chorych po zawale mięśnia sercowego leczonych klopidogrelem jednoczesne stosowanie IPP innego niż pantoprazol jest związane z utratą korzystnego działania klopidogrelu i zwiększonym (5-15%) ryzykiem kolejnego zawału.3,4 Przyczyną tej niekorzystnej interakcji miałaby być wspólna, enzymatyczna (CYP2C19) ścieżka aktywacji klopidogrelu i inaktywacji IPP.

Powszechnie wiadomo, że paracetamol stosowany w zalecanych dawkach pozbawiony jest efektów gastrotoksycznych. Ostatnio okazało się jednak, że łączenie u osób starszych paracetamolu z tradycyjnymi NLPZ, które w założeniu miałoby dać pożądany efekt przeciwbólowy przy mniejszej gastrotoksyczności, w efekcie może zwiększyć ryzyko krwawienia z przewodu pokarmowego.5 To ryzyko jest również podwyższone pomimo stosowania IPP.

Podsumowując, gastroprotekcja u chorych stosujących NLPZ lub leki antyagregacyjne polega dziś na stosowaniu IPP oraz eradykacji H. pylori u pacjentów z wywiadem choroby wrzodowej. Nie wszystkie przypadki można jednak ująć w sztywnych ramach algorytmów. W przypadkach wątpliwych lub skomplikowanych obowiązuje zasada indywidualizacji terapii w zależności od tego, które czynniki ryzyka przeważają. W podjęciu trafnej decyzji diagnostyczno-terapeutycznej bardzo pomaga ścisła współpraca lekarzy różnych specjalności.

Piśmiennictwo

1. Cryer B, Feldman M. Effects of very low dose daily, long-term aspirin therapy on gastric, duodenal, and rectal prostaglandin levels and on mucosal injury in healthy humans. Gastroenterology 1999;117:17-25.

2. Bhatt DL, Scheiman J, Abraham NS i wsp. ACCF/ACG/AHA 2008 expert consensus document on reducing the gastrointestinal risks of antiplatelet therapy and NSAID use: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:1502-1517.

3. Juurlink DN, Gomes T, Ko DT i wsp. A population-based study of the drug interaction between proton pump inhibitors and clopidogrel. CMAJ 2009;180:713-718.

4. Ho PM, Maddox TM, Wang L I wsp. Risk of adverse outcomes associated with concomitant use of clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors following acute coronary syndrome. JAMA 2009;301:937-944.

5. Rahme E, Barkun A, Nedjar H I wsp. Hospitalizations for upper and lower GI events associated with traditional NSAIDs and acetaminophen among the elderly in Quebec, Canada. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:872-882.